Structural Biological Materials

Real organisms use a wide variety of structural materials to give toughness, strength, rigidity, and other desirable material properties to their bodies, both on the cellular (as in cell walls) and tissue (as in bones or exoskeletons) level. Moreover, these materials are rarely homogenous - biological structural materials are almost always composites of more than one material, becoming something greater than the sum of its parts.

Rather than simply take the approach of listing options, this page will aim to explore the general categories of structural biological materials - both real and theoretical - and explain how their particular properties play into how they're used in living creatures.

Polysaccharides (cellulose, chitin, algin, etc.)

Polysaccharides are perhaps the most widespread - and simplest to evolve - structural materials we find in living creatures. Saccharides, especially glucose, are universally used as energy storage in Earth life, and it's likely that alien life - at least, that which shares our basic biochemistry - will do the same. It therefore isn't much of a step to derive your structural materials from the stuff you already use for energy storage!

Most polysaccharides are hydrophobic - even though their component monomers readily dissolve in water.

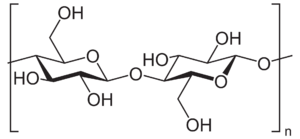

Cellulose, and other simple linear polysaccharides

Cellulose is the simplest and most widespread polysaccharide that sees structural use on Earth, and is likely to be so on alien worlds as well. It's a simple linear chain of β(1→4) linked units of d-glucose - the same molecule nearly all life on Earth uses to store energy. Aliens might use ʟ-glucose instead, but this should have identical mechanical properties.

Contrary to popular belief, cellulose is actually quite flexible, when alone. The rigidity of plant cells - famously with cell walls made out of cellulose - is provided by other materials bonded with cellulose, such as lignin, along with the hydrostatic pressure provided by the water within the cell.

A number of Earth organisms are demonstrated to use mannose, or other simple sugars, in the place of glucose, forming structural polysaccharides such as mannan. Their properties are similar to cellulose - though, how they may bond to other polymers might differ, as we'll discuss later with glucomannans.

Some other organisms, such as oomycetes, use other β-glucans - that is, linear chains of glucose - which have different linkages (such as the β(1→3) linkages of chrysolaminarin) as structural materials. In bulk, their mechanical properties are fairly similar.

Hemicelluloses - heterogenous simple polysaccharides

In plants, cellulose is not found alone - it is typically accompanied by filaments of hemicellulose, otherwise known as polyose, a group of highly heterogenous polysaccharides composed of a semi-random mix of miscellaneous saccharide molecules - predominately arabinose and xylose. The heterogeneity of these fibers inhibits the formation of crystalline structures the way cellulose might form, rendering the result relatively amorphous and weak: if isolated, hemicelluloses would have a gum- or gel-like texture. While that may seem undesirable in a structural material, hemicelluloses perform important functions in plants - in particular, cross-linking cellulose fibers together, adding additional strength and toughness to the resulting matrix.

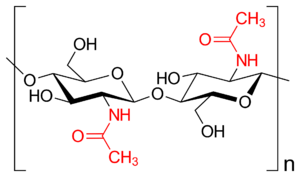

Chitin, and other poly-amino-sugars

Chitin is the second most widespread structural polysaccharide on Earth, and for good reason. Like cellulose, it is a linear chain of single monomers. Rather than being made of simple glucose, however, it is composed of N-acetylglucosamine - an amino-sugar of glucose where one of the hydroxyl groups is replaced by an acetylamino moiety. This acetylamino moiety forms stronger hydrogen bonds with adjacent polymers than the hydroxyl group would, rendering chitin much stronger and slightly more rigid than cellulose - though, it still remains plenty flexible, without other components to rigidify it.

N-acetylmannosamine and N-acetylgalactosamine, derivatives of mannose and galactose, respectively, also exist in nature - to my knowledge, they are not used to form polymers like chitin, but an alien organism may do so!

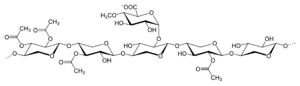

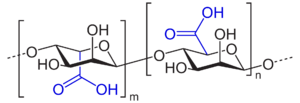

Algin, and other polyuronic acids

Algin, or alginic acid, a polyuronic acid, is a primary structural component of the cell walls of brown algae, such as kelp. It is a polymer of two uronic acids in alternating sequence - β-D-mannuronate and α-L-guluronate. Uronic acids are derivatives of derivatives of saccharides where the hydroxyl group opposite the carbonyl has been oxidized to a carboxyl group, making them a kind of carboxylic acid. This makes polyuronic acids acidic (as implied by the name), which in turn makes them hydrophilic and water-soluble. Since these are long polymers, and typically cross-linked, when used as structural materials, however, they do not exactly dissolve - instead, infiltration of water into the polyuronic acid matrix forms a sort of hydrogel. This is what gives brown algae their soft, gel-like, yet still quite tough structure.

Disaccharide polysaccharides

As demonstrated by algin, above, structural polysaccharides, rather than consisting of a homogenous chain of a single monosaccharide molecule, are instead often composed of two distinct monosaccharides in alternating sequence. This allows the copolymer to have some of the properties offered by both monosaccharides.

A prevalent example in nature is the polysaccharide component of the peptidoglycan in bacterial cell walls, here on Earth - it is an alternating copolymer of N-acetylglucosamine (as found in chitin) and N-acetylmuramic acid, a complex monosaccharide where a lactic acid group has replaced yet another hydroxyl group on N-acetylglucosamine. This lactic acid group is used to provide a strong binding site for the oligopeptide component of the peptidoglycan, which crosslinks the polysaccharide chains.

There are a number of such other examples of alternating polysaccharide copolymers in nature, and there are likely to be yet more combinations in alien organisms!

Branching polysaccharides

As seen above, almost all polysaccharides used for structural purposes in living organisms are linear chains, though branching polysaccharides are commonly used for energy storage. However, some branching polysaccharides do, in fact, see structural use - such as the glucomannans found in some yeasts and plants. Glucomannans consist of a linear chain of mannose units (called a mannan), with short glucose branches. Unlike linear polysaccharides, branched polysaccharides resist forming neat, crystalline structures (as the branches interfere with hydrogen-bond formation between polymers), and thus are able to slide past each other, forming a rubbery, hydrophilic solid.

Polyphenols (lignin, tannin, etc.)

Polyphenols, such as lignin and tannin, are a broad category of biopolymer found almost exclusively in plants on Earth, consisting of many phenol units oxidatively coupled together. Unlike other common structural biopolymers, polyphenols are typically non-linear - instead forming complex 3-dimensional structures. They are also often highly heterogenous, made of many different monomers. This makes it difficult to talk about sub-types of polyphenol, as we have done for polysaccharides - instead, this section will talk about the properties different polyphenols often possess.

Color

Polyphenols' complex 3d structures leads to a variety of interactions with light waves that result in them being typically opaque and strongly colored. While most polyphenols are dark brown - lignin being responsible for the dark brown color of most tree bark - some polyphenols have brilliant colors, such as the anthocyanidins that provide flower petals with vivid reds, purples, and blues.

While structural polyphenols are typically quite separate from pigment polyphenols, an organism that is able to synthesize one is likely capable of synthesizing the other!

Reactivity

Whereas most structural biopolymers are only weakly reactive, polyphenols are quite reactive, specifically to oxidation. This might sound like a vulnerability for a structural material, but polyphenols' reactivity is usually localized to a few specific sites on the molecule. This makes them very good at binding to other structural polymers, like polysaccharides and proteins, at multiple sites, via oxidative coupling. Other structural biopolymers bound by polyphenols in this way tend to become exceptionally hard and rigid - like tree bark.

Resistance to degradation

Some - not all - polyphenols, such as lignins, are exceptionally resistant to bio-degradation, making them very difficult for other living things to break down and digest - and this extends to the other polymers they bind to. This makes them very good at protecting from penetration by parasites or pathogens, and limits the possible predators of organisms that use polyphenol cross-linking in their structures.

Affinity for saccharides

Polyphenols have something of a special affinity for saccharides, and will not only readily bond with them, but also often include one or more saccharide molecules in their structure - such as in tannic acid, a polyphenol composed of phenol branches stemming from a glucose molecule at its center.

Cross-linking proteins (collagens, keratins, sclerotins, etc.)

Proteins - perhaps unsurprisingly, given their ubiquity - are common components of structural biological materials, specifically in the form of cross-linking proteins like keratins or sclerotins, which bond to each other at many different sites, allowing for not only toughness and rigidity but a tunable degree of both - via controlling the frequency of cross-linkages, materials can smoothly vary in rigidity and hardness, often forming distinct gradients in biological structures (such as arthropod cuticle becoming more flexible around the joints).

Most cross-linking structural proteins tend to be brown to black in color, though are not particularly opaque, and some can be outright colorless. Their versatility also lends themselves to the creation of complex microstructures resulting in vivid structural colorations, and tissue that includes them often also plays host to a variety of pigments that add their own colors to the material.

Collagens

Collagens are the primary family of structural proteins found in all metazoans, though they are most prominent in the deuterostomes - in protostomes, many of the functions typically performed by collagens are instead performed by chitin. In mammals, collagens make up 25-35% of all proteins in the body! They make up the connective tissue, while also adding strength to other tissues (such as blood vessels) throughout the body, and also providing the matrix on which hydroxyapatite is deposited to form bone and cartilage in vertebrates.

Collagen consists of a left-handed triple helix of elongated peptide chains. About half of its amino acid content is glycine and proline alone, which appear to play a role in binding the three components of the helix together. In addition, sites throughout the chain are saturated in hydroxylysine - a hydroxylated derivative of the amino acid lysine. It is by these hydroxylysine sites that collagen helixes are cross-linked - via aldol condensation, strong covalent bonds are formed through conjugated enone moieties between the hydroxylysine sites on adjacent collagen helixes. This binds the adjacent helixes together very strongly, while still allowing hydrolysis of the linkages when they must be split apart, unlike certain other structural proteins.

Unlike most structural proteins, collagen appears colorless, or sometimes white. It is also extremely flexible - collagenous tissue must rely on other components to add hardness and rigidity, if necessary.

Keratins

Keratins are the primary family of structural proteins found in vertebrate integument - composing hair, nails, feathers, scales, etc, while also reinforcing the epithelial tissue (the outermost layer of the organs and blood vessels). There are two primary categories of keratin - α-keratins, which are found in all vertebrates, and β-keratins, which are found only in sauropsids. The primary difference between these is that α-keratins form double-helix filaments and are more flexible, whereas β-keratins form β-pleated sheets and are significantly harder and more rigid.

Both types of keratin crosslink by means of disulfide bridges - they contain large amounts of the amino-acid cysteine, which bonds to cysteines on adjacent keratin polymers via the sulfur. These bonds are very strong and rigid, and, as mentioned before, the precise degree of hardness and rigidity can be precisely controlled by determining the frequency of disulfide bridges. The presence of so much sulfur-containing cysteine is why heavily-keratinized tissues - like human hair - smell pungent when burned.

Sclerotins

Sclerotins are another widespread family of structural proteins, found primarily in arthropods but also some annelids. Sclerotins are a much broader family of proteins than keratins, and do not have a particular identifiable geometric structure, unlike the α-helixes and β-pleated sheets of keratins. They are also not bonded by disulfide bridges - instead, they are cross-linked by a process, called sclerotization, similar to what is done to tan animal hide into leather.

Sclerotin proteins contain large numbers of free amine and thiol groups, which tend towards oxidative reactions with other molecules. In the process of sclerotization, quinones are enzymatically introduced to tissue containing large numbers of sclerotins, typically by enzymatic action on dopamine-derivatives such as N-acetyldopamine. These quinones then react, forming strong covalent bonds, with the amine and thiol groups on the sclerotins, cross-linking them together into an exceptionally tough, hard, and rigid material. Like keratins, the exact degree of hardness and rigidity can be controlled, this time via the amount of quinones introduced into the tissue.

Sclerotization is effectively non-reversible - cross-linked sclerotins being extremely hard to break apart - and thus organisms must shed sclerotinized parts if they need to change them, hence the necessity of molting in arthropods.

Some annelids, such as the intimidatingly-named bloodworm, have special sclerotins which bind metal ions, such as copper and iron, prior to undergoing sclerotization. This results in unique metal-composite structures which are exceptionally hard and strong.[1]

Other cross-linking proteins

Other cross-linking proteins are found in other clades, though none as archetypical and widespread as keratins and sclerotins.

For example, cephalopod mollusks possess their own particular cross-linking proteins that add hardness and rigidity to their beaks, operating in a two-tiered system - they are, unfortunately, absent a catchy name like keratins and sclerotins, and are instead simply referred to as chitin-binding beak proteins (CBPs) and histidine-rich beak proteins (HBPs). CBPs simply bind to multiple chitin chains at both ends, forming cross-links between them. HBPs add a second tier to this matrix, and bond to both CBPs and each other, forming an additional set of cross-links to add even more strength, hardness, and rigidity to the result.[2]

Alien organisms may be expected to exhibit yet more variations on the common motif of proteins cross-linked together, unseen on Earth - instead of directly using one found on Earth, it may be better to simply specify a, say, "keratin-like protein"!

Biominerals

While all the structural materials discussed previously - and those which will be discussed after - are polymers, mineral crystals also play a major role in structural biological materials. All biominerals excel at adding hardness, strength, and rigidity to biological materials - for obvious reasons, heavily-biomineralized tissue cannot be flexible; although semi-flexible, partially-biomineralized tissue, such as cartilage in vertebrates, is observed in nature.

In addition to performing structural functions, biomineralized tissue also often functions as a reservoir of minerals - such as calcium, phosphate, and sulfate - that are essential for biological function. In fact, many heavily-biomineralized structures are believed to be evolutionarily derived from simple mineral reservoirs - it is believed that the spin in vertebrates originates from a the use of the primitive notochord for calcium storage, for instance.

Most biominerals are salts, and they are typically classified first by their anion, then their cation.

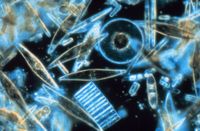

Silicates

Silicates, otherwise known as common glasses (literally, like the kind in your window), are perhaps the most common and widespread class of structural biominerals on Earth, having independently evolved countless times throughout the tree of life. This may seem surprising, given that you probably know of very few living things that are made out of glass - and that's because almost all organisms that use silica as a structural biomineral are unicellular. Of the multicellular, macroscopic clades that use silica as a structural material, there is only one that uses it as primary structural material - the Hexactinellid sponges, otherwise known as "glass sponges." However, some plant clades, such as horsetails, do make use of it as a minor component.

Silicates are also one of the few biominerals that are not typically found in the form of a salt - instead being typically formed of silica (SiO₂) in its various crystalline forms. Silica is virtually impossible for any living organism - including plausible alien organisms - to metabolize for any purpose, as it requires extreme amounts of energy to break down into silicon and oxygen, and doesn't react with much of anything - as a result, unlike many other biominerals, it is solely' a structural material. On the other hand, this strength and non-reactivity make it exceptional for that very purpose!

Silicate biomineralization is ususally performed by precipitating silic acid, dissolved in water, onto a matrix of structural filaments. This not only results in a very strong structural material, it is also, energetically, exceptionally cheap - organisms that use silica as a structural material spend only a fraction of the energy building such structures that other structural materials require.

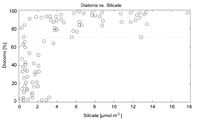

This, however, means that building biological structures out of silica is strictly limited by the bioavailability of silicic acid - and silica does not, typically, readily dissolve in water, making this quantity limiting indeed. In fact, fierce competition over silicic acid is why, today, Heaxactinellid sponges are limited to deep-water environments, even though fossil evidence indicates they were once found in shallow waters - the evolutionary ascendancy of the unicellular diatoms, which build their frustules out of silica, depleted the surface waters of silicic acid, driving other shallow water organisms that utilized it to extinction. So, if you wish to have much larger, more complex, more numerous organisms use silicate biominerals, something must lead to a greater bioavailability of silic acid in the environment - for example, silica is significantly more soluble in water that contains a significant percentage of ammonia!

Carbonates

Carbonates are another exceptionally common class of biominerals, defined by the presence of the carbonate anion (CO₃⁻²). Due to the ubuiquity of both carbon and oxygen in biology - and in the environment in general - it is readily provided as an anionic component of biominerals.

Though sodium and potassium cations are exceptionally common in biology, sodium carbonate and potassium carbonate are both highly soluble in water; this makes them inadvisable as structural materials, as they will simply dissolve if they get wet (and water-born organisms are, essentially, always wet)!

Calcium carbonate

Typically, the cation in carbonate biominerals is Calcium (due to both its relative commonality and biological essentiality for most Earth life), and it is typically in the form of calcite (as in foraminifera, coccolithophores, and echinoderms) or aragonite (as in mollusk shells and coral skeletons), but calcium carbonate has also been observed in life in both vaterite and amorphous forms as well. Notably, presence of magnesium inhibits the formation of calcite - if significant magnesium is present in biomineral, it will almost certainly be in the aragonite form.

Calcium carbonates are highly soluble in acidic solutions - so on worlds where the waters are relatively acidic, calcium carbonate biominerals can not be expected to be used!

-

Calcite tests of foraminifers.

-

Cutaway of a nautilus shell, made of nacre - tiny aragonite plates layered on top of each other.

Magnesium carbonate

Magnesium is almost as widely used in biology as calcium, and is about half as common as calcium in Earth's crust and oceans. In fact, calcium carbonates frequently contain some amount of magnesium as the cation instead.

Magnesium carbonate - that is, where magnesium is by far the most predominant cation - will almost always be in the form of magnesite. If there are roughly 3 magnesium cations to each calcium cation, it will form huntite. If, instead, the mineral is composed of roughly equal portions of calcium and magnesium, it will form dolomite instead. Notably, higher-magnesium content carbonates are significantly less soluble in acidic solutions than calcium carbonate, meaning magnesite, huntite, and dolomite biominerals may be preferred on worlds with acidic oceans!

Dolomite and magnesite are also harder than aragonite and calcite, making them potentially stronger as structural components than the calcium carbonates. Huntite is, unfortunately, quite weak, making it generally inferior for structural purposes to both the calcium carbonates and the other magnesium carbonates. That huntite is in the middle of the transition between dolomite and magnesite means it will likely be somewhat more difficult to evolve near-pure magnesite biominerals for structural purposes than dolomite.

Manganese carbonate

Manganese is yet another biologically essential cation, though it is a quarter as common as calcium and half as common as magnesium. It is especially common on and around hydrothermal vents. Like with magnesium, it often accompanies calcium carbonates (and vice versa) in nature. Manganese carbonate is almost always found in the form of rhodochrosite - which, interestingly, has an intrinsic deep-red to pink color, with higher calcium content leading to lighter shades. Rhodochrosite is not observed as a structural biological material in nature, to my knowledge, but it is entirely plausible that alien organisms might use it as such.

Rhodochrosite is of comparable hardness to dolomite and magnesite, but also possesses the interesting property of perfect cleavage - that is, when rhodochrosite is cleaved along one of its cleavage planes, it leaves a perfectly smooth cut. This makes it resistant to fracture - it is almost impossible to fracture, rather than cut, in combination with its relative softness, in fact - and exceptionally difficult to cut along an axis that is not a cleavage plane. Since organisms can control the orientation of individual crystals when forming biominerals, this allows the possibility of composites with very particular rhodochrosite crystal orientation that are much tougher and stronger than expected.

Rhodochrosite is also denser and heavier than calcium and magnesium carbonates, with a specific gravity of 3.7 compared to the ~3.0 possessed by the others. This may be an advantage or disadvantage, depending on the application.

Manganese carbonate is also found in the form of Kutnohorite, when found with calcium, manganese, and iron. It is typically a pale, opaque pink. It has roughly the same hardness as rhodochrosite, but a lower specific gravity of 3.12.

Iron, copper, and zinc carbonates

Iron, copper, and zinc, while not as common as either calcium or magnesium, are biologically essential metals; and, indeed, they do appear as components of other biominerals, though I am unaware of any specific examples of iron carbonate or copper carbonate biominerals, specifically.

Iron carbonate is typically in the form of siderite, though compounded with calcium and some amount of manganese it instead forms ankerite. Both are of comparable hardness to dolomite, magnesite, and rhodochrosite; siderite has a hardness ranging from 3.75 to 4.25, while ankerite has a hardness ranging from 3.5 to 4. Siderite is substantially heavier than even rhodochrosite, with a specific gravity of 3.96, though ankerite has roughly the same specific gravity as calcium and magnesite carbonates.

Copper carbonates are only found in the carbonate hydroxide forms, specifically azurite and malachite. The difference is the ratio of hydro carbonate to hydroxide; azurite has a roughly 1:1 ratio, while malachite has a ratio of roughly 1 carbonate:2 hydroxide. Azurite is intensely blue, and malachite is intensely green; azurite's hardness ranges from 3.5 to 4, while malachite's ranges from 3.5 to 4.5. Azurite will slowly weather to malachite, when exposed to atmosphere.

Zinc carbonate is found in the form of smithsonite when it is the sole cation, or in the form of minrecordite when compounded with equal amounts of calcium. With hydroxides, it can be found in the form of hydrozincite; with hydroxides and copper, it can be found in the forms of rosasite and aurichalcite. Smithsonite is quite hard, with a hardness of about 4.5, and a very high specific gravity of approximately 4.5. Minrecordite, technically a variety of dolomite, has roughly the same properties as dolomite. Hydrozincite is, unfortunately, not very hard, and thus not particularly suitable for structural use, as is auricalchite; rosasite, however, has a high hardness of 4 and a high specific gravity of 4-4.2.

Phosphates

Phosphates, while not as common as carbonates (either in biominerals or in life in general), possess two properties which make them especially desirable as biominerals.

First, phosphate is itself an absolutely essential nutrient for all life on earth, and the same can be expected to be so as well for extraterrestrial organisms which have even remotely similar biochemistry to earth organisms, due to being the primary source of the element phosphorous. Therefore, phosphate biominerals serve not only as a reservoir of whatever cation the phosphate is paired with, but of phosphate as well.

Second, phosphate minerals are generally harder - and thus make for stronger composites - than carbonates, typically ranging from around 5 to 6 in hardness, compared to carbonates' typical 3 to 4, while being no heavier.

As with carbonates, sodium phosphate and potassium phosphate are too soluble in water to be used for structural biominerals - although, surprisingly, there are some sodium-containing phosphates that are insoluble enough to be viable.

Apatites - calcium phosphates

Calcium phosphates, otherwise known as apatites, are the most common phosphate biominerals here on Earth, again owing to calcium's biological essentiality and relative commonality. Apatites are always found with a third ion in addition to the calcium and apatite, and this can be one of three different ions - hydroxide (OH⁻), fluoride (F⁻), or chloride (Cl⁻). All apatites have a hardness of 5 (for which they are the defining mineral) and a low specific gravity of 3.16-3.22.

Hydroxyapatite, an apatite with hydroxide (OH⁻), is the most common biomineral apatite on Earth - and also likely to be so on alien worlds, given the relative rarity of fluorine and chlorine. It is the primary mineral constituent of vertebrate bone (though some carbonates are also included), and is also found in a the clubbing appendages of the peacock mantis shrimp.

Fluorapatite, a less biologically common apatite with the fluoride ion (F⁻), is actually quite commonly found in Earth life - particularly because fluoride, in solution, will readily replace the hydroxide in hydroxyapatite, transforming it into fluorapatite. That fluorapatite is slightly stronger and more chemically resistant than hydroxyapatite is the reason why, here on Earth, water in developed countries has fluoride added - the replacement of hydroxyapatite in your teeth with fluorapatite helps maintain dental health. Similarly, we can expect alien organisms to incorporate as much fluorapatite over other apatites as there is fluoride bioavailable to do so.

Chlorapatite, an even less biologically common apatite with the chloride ion (Cl⁻), is again, actually found in Earth life - like fluoride, it will replace hydroxide, but it will in turn be replaced by fluoride. It is mostly irrelevant on Earth, forming only in environments particularly deficient in fluorine, but if an alien world has significantly more chlorine than Earth, it may become a major biomineral.

Whitlockite - calcium magnesium/iron phosphate

Whitlockite is a distinct form of calcium phosphate that forms with the introduction of significant amounts of magnesium and iron, having the overall formula Ca₉(MgFe)(PO₄)₆PO₃OH, though the amounts of magnesium and iron can be varied more than this formula suggests. It is sometimes considered a subtype of apatite.

Whitlockite has a slightly lower specific gravity than (other) apatites, at 3.13, and is just as hard. Its crystalline structure is ditrigonal pyramidal, instead of the dipyramidal arrangement found in (true) apatites; it has a noticeably different texture as a result, and displays no cleavage. It is found in some parts of biological systems where one would ordinarily find hydroxyapatite, on Earth organisms.

Manganese phosphates

Manganese, already mentioned to be a biologically important cation, forms a number of interesting - and potentially biologically useful - minerals with phosphate, typically including other cations, particularly calcium and iron, as well.

Graftonite - iron/manganese/calcium phosphate

Graftonite is an interesting phosphate mineral with a mixture of iron, manganese, and calcium, in variable proportions, as the cation, and no additional anions such as hydroxide, unlike in apatite. It has roughly the same hardness as apatite, with a rating of 5, and has a significantly higher specific gravity of approximately 3.7. Unlike the colorless-to-white apatites, due to the inclusion of manganese and iron, it has a red-brown to pink color, depending on the exact proportions of each cation.

Notable for its lack of hydroxides or fluorides, unlike most other phosphates.

Triplite and Triploidite - manganese/iron phosphate hydroxy/fluoride

Triplite and triploidite are two related phosphate minerals formed with a mixture of manganese and iron in variable proportions. It appears a pinkish red-brown in color, again varying somewhat towards red-brown or pink depending on the ratio of manganese to iron. The two names are essentially describing the two ends of a spectrum of minerals, with triplite referring to fluoride-heavy instances, while triploidite refers to hydroxide-heavy instances. The mineral's hardness is roughly equivalent to apatite, but varies depending on the ratio of hydroxide to fluoride, falling as low as 4.5 and reaching as high as 5.5.

Natrophilite - sodium manganese phosphate

Natrophilite is a particularly common phosphate mineral with both sodium and manganese as cations. It is a slightly pinkish yellow in color. It is slightly less hard than apatite, but still quite hard - rating between 4.5 and 5 on the Mohs scale - and has a slightly higher specific gravity of 3.41. Despite its slight weakness in comparison to apatite, it is still harder than all carbonate minerals, and is notable for being a sodium-containing mineral that is not particularly soluble in water - although it still readily dissolves in acidic solutions.

Alluaudite - alkaline manganese phosphate (+iron/magnesium)

Alluaudite is a somewhat complex mineral, relatively common - although mostly abiogenic - on Earth, with the complex chemical formula (Na,Ca)Mn²⁺(Fe³⁺,Mn²⁺,Fe²⁺,Mg)₂(PO₄)₃. In essence, this is a phosphate mineral, with a manganese cation, a sodium or calcium cation, and two cations of iron, (more) manganese, or magnesium. As befitting its variable composition, it has a variable coloration depending on composition, including dirty yellows, yellowish browns, and grayish greens.

This variable composition makes it surprisingly plausible as a biomineral - it could serve as a reservoir of a variety of different essential minerals for a living organism, in addition to serving a structural purpose.

It is notably harder than apatite, with a hardness of 5 to 5.5 on the Mohs scale. It has a somewhat greater specific gravity, from 3.4 to 3.5.

Sulfates

While much less common than silicates, carbonates, or phosphates, some organisms do use sulfate minerals for structural functions. Sulfate is, like phosphate, an essential biomineral for a variety of organism; though, unlike phosphates, sulfates are quite structurally weak, more comparable to carbonates. Perhaps surprisingly, this is one class of biomineral for which calcium is not the most common cation - calcium sulfate minerals are generally quite weak, and fairly soluble in water, making them poorly suited for structural purposes. Instead, the predominant cations that appear with sulfates are, surprisingly, the relatively rare barium and strontium, giving sulfate biominerals astoundingly high specific gravities compared to most other biominerals.

Baryte - barium sulfate

Barium sulfate is used as a reinforcing biomineral in a variety of clades across the tree of life on Earth, including some close relatives of the plants (embryophtes), such as the Charophyceaen and Zygnemophyte algaes. It is relatively colorless, and has a Mohs scale hardness of 3-3.5. It has a specific gravity of 4.3-5 - bare in mind, no non-sulfate biomineral we have described thus far has had a specific gravity above 4!

Rather than storing barium for later biological use, baryte, as a biomineral, tends to serve the purpose of keeping barium away - barium is toxic, and not particularly biologically useful, to nearly all living organisms. By joining it with sulfate, barium ions are precipitated out of water into baryte, where they both can no longer harm the organism and also can provide a convenient source of structural material.

Celestine - strontium sulfate

Celestine a prettily-named and quite pretty looking sulfate mineral, is, despite its seeming oddity, one that is actually found on Earth - the Acantarea clade of radiolarians make their hard skeletons out of celestine, the high specific gravity of which helps them cling to ocean floors, avoiding being carried away.

Celestine has a very pretty light blue color, a hardness of 3-3.5, and a very high specific gravity of approximately 3.95. It also happens to fluoresce yellow-to-light-blue in the UV range.

Metal Oxides and Sulfides

A few organisms, in need of exceptionally tough and hard biominerals, have evolved the use of metal oxides and sulfides for such a purpose. Unlike metal salts, they do not make particularly good reservoirs of essential metals for other biological purposes - they are quite strongly bound, and thus are, like silicates, almost solely used as structural materials. However, they do also potentially have one other, interesting use - many of these minerals (particularly magnetite and greigite) are ferromagnetic, and can function as a sort of biological compass, in special bodies called magnetosomes.

Magnetite and Goethite - iron oxides

Magnetite and Goethite are iron oxide minerals that are both found as biominerals here on Earth - magnetite in the teeth of chitons, and goethite in the teeth of limpets. It is no accident that both cases involve teeth - both clades scrape organic matter, such as algae and bacteria, from hard rocks and sediment, and need teeth that are exceptionally hard and resistant to wear.

Magnetite has an exceptionally high Mohs scale hardness of 5.5-6.5, and a very high specific gravity of approximately 5.18. Goethite has slightly less hardness, with 5-5.5, and a lower specific gravity of 3.3-4.3. Both are a glossy black color.

Pyrite and Greigite - iron sulfides

Pyrite and Greigite are iron sulfide minerals that both, again, are found as biominerals here on Earth - though, this time, in the defensive adaptions of gastropod molluscs living near hydrothermal vents, which reinforce their shells with these minerals.

Pyrite has an absolutely outstanding (for a biomineral) Mohs scale hardness of 6-6.5, and a high specific gravity of 4.95-5.10. It, infamously, looks quite similar to elemental gold - having the common name "fool's gold." Greigite has the more moderate hardness and specific gravity values of 4-4.5 and 4, respectively, and appears a blue-black color.